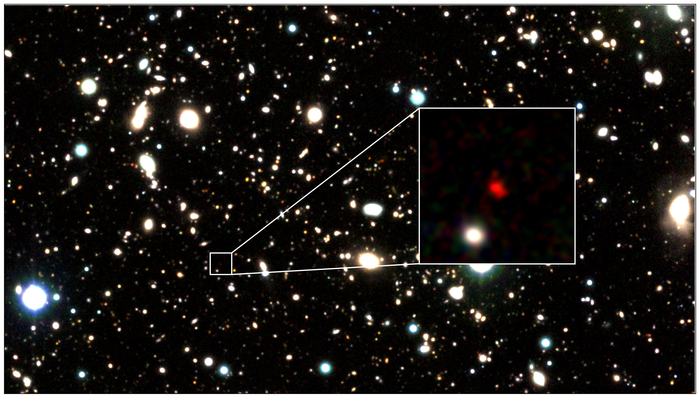

An international team of scientists has just spotted the most distant galaxy to date. Called HD1, the galaxy candidate is about 13.5 billion light-years away and was described Thursday in Astrophysical Journal.

This is interesting in and of itself, but it gets better; it may be home to “Population III” stars. These are postulated to be the first kind of stars ever born which have never been observed, until possibly now. Another view is that the galaxy could also be home to a supermassive black hole roughly 100 times the mass of our Sun.

“Answering questions about the nature of a source so far away can be challenging,” said Fabio Pacucci, lead author of the MNRAS study, co-author in the discovery paper, and an astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics.

“It’s like guessing the nationality of a ship from the flag it flies, while being far away ashore, with the vessel in the middle of a gale and dense fog. One can maybe see some colors and shapes of the flag, but not in their entirety. It’s ultimately a long game of analysis and exclusion of implausible scenarios,” he added.

The newly discovered galaxy is very bright in the ultraviolet part of the electromagnetic spectrum. This is odd but could be explained by, “some energetic processes are occurring there or, better yet, did occur some billions of years ago,” Pacucci says.

When it was first discovered, the research team believed HD1 would be just another standard starburst galaxy – a galaxy that is creating stars at a high rate. However, after trying to calculate the number of stars the galaxy contained they found that they would be born at “an incredible rate”, more than 100 stars every single year. “This is at least 10 times higher than what we expect for these galaxies,” Pacucci explained.

That’s when the team began suspecting that HD1 might not be forming normal, everyday stars.

“The very first population of stars that formed in the universe were more massive, more luminous, and hotter than modern stars,” Pacucci says. “If we assume the stars produced in HD1 are these first, or Population III, stars, then its properties could be explained more easily. In fact, Population III stars are capable of producing more UV light than normal stars, which could clarify the extreme ultraviolet luminosity of HD1.”

This is where some members postulated that the answer could be a supermassive black hole instead. As the black hole eats its way through the mass of the galaxy, high-energy photons may be emitted by the region around the black hole.

If true, this would make it the earliest supermassive black hole yet discovered by our species. The black hole would also represent a very early one close to the time of the “Big Bang” compared to the current record-holder.

“HD1 would represent a giant baby in the delivery room of the early universe,” says Avi Loeb an astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics and co-author of the MNRAS study. “It breaks the highest quasar redshift on record by almost a factor of two, a remarkable feat,” he added.

The discovery took a lot of digging through data

The new galaxy was unearthed after more than 1,200 hours of observing time with the Subaru Telescope, VISTA Telescope, UK Infrared Telescope, and Spitzer Space Telescope.

“It was very hard work to find HD1 out of more than 700,000 objects,” says Yuichi Harikane, an astronomer at the University of Tokyo who discovered the galaxy. “HD1’s red color matched the expected characteristics of a galaxy 13.5 billion light-years away surprisingly well, giving me [a few] goosebumps when I found it,” they added.

But, this was not all it took. The international team needed to conduct follow-up observations using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to confirm the distance – which is 100 million light-years further than GN-z11, the current record-holder for the furthest galaxy.

Further data will also need to be obtained using the James Webb Space Telescope, the research team to verify its distance from Earth. But, if current calculations prove correct, HD1 will be the most distant, and oldest, galaxy ever recorded.

This data will also help clear up whether the galaxy contains very old stars or a supermassive black hole too.

“Forming a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, a black hole in HD1 must have grown out of a massive seed at an unprecedented rate,” Loeb says. “Once again, nature appears to be more imaginative than we are.”

Study abstract:

We present two bright galaxy candidates at z~12-13 identified in our H-dropout Lyman break selection with 2.3 deg2 near-infrared deep imaging data. These galaxy candidates, selected after careful screening of foreground interlopers, have spectral energy distributions showing a sharp discontinuity around 1.7 um, a flat continuum at 2-5 um, and non-detections at <1.2 um in the available photometric datasets, all of which are consistent with z>12 galaxies. An ALMA program targeting one of the candidates shows a tentative 4sigma [OIII]88um line at z=13.27, in agreement with its photometric redshift estimate. The number density of the z~12-13 candidates is comparable to that of bright z~10 galaxies, and is consistent with a recently proposed double power-law luminosity function rather than the Schechter function, indicating little evolution in the abundance of bright galaxies from z~4 to 13. Comparisons with theoretical models show that the models cannot reproduce the bright end of rest-frame ultraviolet luminosity functions at z~10-13. Combined with recent studies reporting similarly bright galaxies at z~9-11 and mature stellar populations at z~6-9, our results indicate the existence of a number of star-forming galaxies at z>10, which will be detected with upcoming space missions such as the James Webb Space Telescope, Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, and GREX-PLUS.